Your Most Important Piece of Training Gear - Part 1 (Lifting Gear Series)

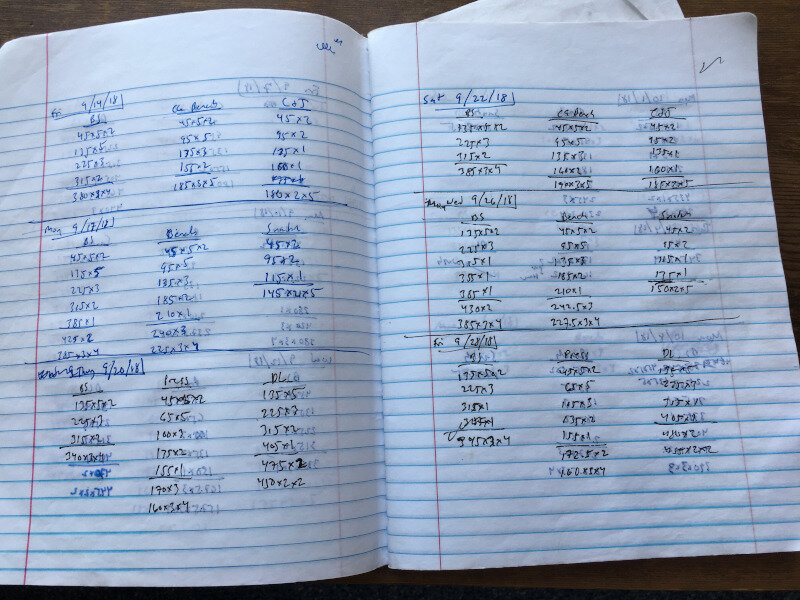

/Today, we're going to talk about your most important piece of training equipment. It’s not your belt, shoes, or wrist wraps - it’s not even the barbell or the squat rack. Your belt, shoes, and wraps can be easily replaced, and people train on different squat racks and with different barbells all the time. The one item that cannot be replaced - the one thing that is specific to you - is your training log.

In Part 1 of this mini-series, we’re discussing why the training log is important and why you should keep one, and in Part 2, we’ll cover how to set one up and correctly use it.

Be sure to check out the included videos as they also cover some additional material not included in this article.

This is the sixth article in our “Lifting Gear” series. Click below to read the previous articles in the series:

Exercise vs Training

Your training log is important since it’s specific to you, but it’s important for a number of other reasons as well. For starters, the training log separates exercise from training.

There’s nothing wrong with exercising, and it is certainly much better than doing nothing at all. However, exercising is what you do when you want to get hot, you want to get sweaty, you want to get tired, and you want to feel like you’ve accomplished something. Training, on the other hand, is what you do when you actually want to accomplish something, and that’s what we’re focused on.

Your Training History

Your training log is also important because it contains your history. As a result, it of course contains your lifts, warm-ups, work sets, etc., but it holds more than that. It tells you how training went on a given day - you can write down notes about your training sessions, and I encourage you to do precisely this. Notes such as “Today was a great day,” “Today was terrible,” or “185 for work sets felt awfully heavy!” are all examples of what you might write in your log.

Remember - someday 185 lb will just be a warm-up weight, and on that day, it will be very satisfying to look back and remember when 185 lb was a challenging work weight.

Your Training Compass

Because you train, you have a program and a plan. You have goals, and because your training log contains your history - i.e., where you’ve been - it also functions as your compass and helps guide you in the direction you want to go.

The log works as a compass in two ways - first, before you leave the gym each day, plan your next session. You want to walk into the gym for your next workout knowing what you’re going to hit for your work sets, so write all of that down before leaving the gym.

Second, the log functions as a compass because you’re going to write down your goals: “I want to squat 315 lb,” “I’m going to get my first chin-up this year,” or “I want to bench 225 lb at my next meet” are all solid examples of goals to write in your training log. These help guide you, motivate you, and make the process much more gratifying when you achieve these milestones.

Your training log is important - it separates training from merely exercising, it contains your history, and it’s your compass as you go forward. Next, it’s time to learn how to keep a log, so in Part 2, we’ll cover precisely how to go about setting up and utilizing your training log. In the meantime, we hope this helps you get stronger and live better.

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)

If you found this helpful, you’ll love our weekly email. It’s got useful videos, articles, and training tips just like the one in this article. Sign up below, and of course, if you don’t love it, you can unsubscribe at any time.

At Testify, we offer small group training, private coaching (in-person or remotely via Zoom), online coaching, and form checks. Would you like to get quality coaching from a Starting Strength Coach?

The BEST Warm-up for Barbell Training (Plus an EASY Math Trick to Help!)

/How can you warm-up in a simple and efficient manner? It’s not a particularly thrilling topic, but it’s important, and if you’ve been using a percentage chart or an app to help you warm-up, well, you want to stop that right now.

Warm-up charts and apps can indeed be useful when you’re new to lifting, but they’re the diapers of the lifting world - really useful to have in the beginning, but in the long run, life is a lot simpler, cleaner, and better if you outgrow them. Let’s cover the basic criteria of how to structure a warm-up (and there are a number of videos included that go more in depth), and at the end, we’ll go over a math shortcut that’s awfully handy.

#1: Your Warm-up Should Prepare You

There are three warm-up criteria, and the first is that your warm-up should prepare you for your work sets. To do this, the warm-up sets get heavier in roughly even jumps.

#2: Your Warm-up Should Not Exhaust You

Your warm-up needs to get you ready for the work sets, but you don’t want to waste any unnecessary energy during the warm-up, so you will taper the number of reps in your warm-up sets. A rep scheme like 5-3-2-1 works quite well, and although at the beginning of your strength training career, you might not need that many sets, that type of scheme gets the main idea across quite well.

#3: Your Warm-up Should Be Convenient

In other words, the weights you choose for each set should be relatively convenient and easy to load on the barbell. This is where percentage charts and apps really miss the boat - since they don’t take this factor into account, you’ll get a number like - for example - 90 lb for one of your warm-up weights. Don’t do 90 lb - instead, simply use 95 lb since loading a 25 lb-plate on each side of the bar is much simpler than loading two 10-lb plates and one 5-lb plate on each side.

Also, if you’re using a chart or an app to warm-up, every time your work weight changes, all of your warm-up weights then change too (since they are calculated as a percentage of the new work weight). If you construct your own warm-ups, however, you’ll find that you usually only need to change one or two warm-up sets from session to session.

Warm-ups Are Not Precise . . . Mostly.

As you get stronger, more and more of your warm-ups will stay roughly the same from session to session (as mentioned above), and more of your warm-up weights will be built around the bigger plates such as 25-lb and 45-lb plates. On the other end of things, you’ll find that you don’t need to use 2.5-lb plates for your warm-up as warm-ups don’t need to be terribly precise. You might find that you don’t even use 5-lb plates for most of your warm-ups, and you certainly don’t use 1.25-lb plates for your warm-ups.

The 90% Approach

However, as the warm-up progresses to your last warm-up set, it might be time to be a bit more precise, and with that in mind, performing 90% of your work weight for one rep as your last warm-up set is a very reasonable approach (not the only approach, but a pretty solid one). With this in mind, let’s take a look at a sample squat warm-up using 285 lb as the work weight, and we’ll cover an easy way to calculate 90% of 285 as well (Put the calculator down. Now.).

Sample Warm-up with Work Weight of 285 lb

Starting with the empty bar, our lifter performs two sets of 5 reps and then moves on to 135 lb for his next warm-up set (i.e., he adds a 45-lb plate to each side), so we have the following:

45 x 5 x 2

135 x 5

At this point, he adds a 25-lb plate to each side to reach 185 lb and performs a set of 3 reps:

45 x 5 x 2

135 x 5

185 x 3

After this, jumping to 225 lb (i.e., two 45-lb plates on each side) is a reasonable jump for someone who squats 285 lb, so he does this and performs a set of 2 reps, giving us the following thus far:

45 x 5 x 2

135 x 5

185 x 3

225 x 2

If you ignore the empty bar sets, you’ll note that we’re using the 5-3-2-1 scheme covered earlier in this article. The question now becomes, “Can he go from 225 lb directly to 285 lb, or should he do one more warm-up set?” He might be able to make that jump without any trouble, but it’s a rather big jump (bigger than the previous two jumps, which is usually a bad sign), and putting in one last single at about 90% of his work weight is probably a wise move.

The catch is this: Don’t actually calculate 90%.

Math Shortcut

Of course, you are indeed going to figure out 90% of the work weight, but you’re going to do it - mentally - in a roundabout manner, and by doing so, you’ll have done it faster than you would have if you went over and grabbed your phone, calculator, abacus, etc.

Here’s how to find 90% of a number: Subtract 10% of the number instead. As you may or may not remember from your grade school days, finding 10% is easy as it just involves moving a decimal point . Breaking this down, we see the following steps:

10% of 285 is 28.5

28.5 is a silly number. Round that to 30 (remember, warm-ups don’t need to be that precise).

285 - 30 = 255

Thus, our lifter will squat 255 lb for one rep for his last warm-up set, which means his entire warm-up is as follows:

45 x 5 x 2

135 x 5

185 x 3

225 x 2

255 x 1

At this point, he’s all warmed up, and a huge bonus is that his next squat workout of 290 lb can use the exact same warm-up, with the exception being that he might choose to do 260 lb instead of 255 lb for his last warm-up single.

With a little bit of practice, this method of constructing your warm-up will be quicker, easier, and require less thinking than that old chart or that silly app.

As always, we hope this helps you get stronger and live better.

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)

If you found this helpful, you’ll love our weekly email. It’s got useful videos, articles, and training tips just like the one in this article. Sign up below, and of course, if you don’t love it, you can unsubscribe at any time.

At Testify, we offer small group training, private coaching (in-person or remotely via Zoom), online coaching, and form checks. Would you like to get quality coaching from a Starting Strength Coach?

The LPP Rule: Fewer Barbell Loading Mistakes

/(A Blast from the Past article originally posted on 01/21/22)

The name in the following story has been changed to protect the guilty . . .

This is not 140 lb . . . and Sally knows better.

One of our lifters - Sally - needed to squat 140 lb for her work sets. However, Sally didn’t want to spend the effort necessary to put a 45 lb plate on each side of the barbell. Bear in mind that Sally squats over 200 lb and deadlifts nearly 300 lb, so it wasn’t as though lifting a 45 lb plate was very difficult for Sally - she just didn’t want to do it.

Consequently, Sally had to use far more plates to load her bar than she normally would have used had she chosen to use a 45 lb plate, and as a result, she made a barbell math mistake and ended up squatting 130 lb for a couple of sets instead of 140 lb. When I noticed this, I pointed it out to her and also pointed out that she now needed to load the correct weight and perform her work sets.

What’s the moral of this story? All lifters make math errors when loading the barbell every now and then, but you can greatly reduce your chances of loading (and lifting!) the wrong weight if you follow one simple rule:

The LPP Rule: Always put the Largest Possible Plate on the bar.

(I recommend watching the included video for a demonstration as well as explanation)

For example, if you want to squat 140 lb (using a 45 lb bar), simply put a 45 lb plate on each side followed by a 2.5 lb plate on each side. Do NOT use some silly combination of plates such as a 25, two 10s, and a 2.5 on each side, or worse yet, a 25, a ten, two 5s, and a 2.5. The list of terrible combinations goes on and on, and this is exactly the problem.

If you always put the largest possible plate on the bar (the LPP Rule), then there is only one possible combination of plates that will produce the correct weight on the bar. If you don’t utilize this method, there are myriad combinations that will get you the correct weight, and with this greater number of possibilities comes a correspondingly greater number of ways that you can screw up the math and misload your bar.

With the LPP Rule, not only are there far fewer ways to make a mistake, but you’ll also benefit from always building your bar math around “milestone weights” such as 95 lb (one 25 on each side), 135 lb (one 45 on each side), 185 lb (one 45 and one 25 on each side), etc. These milestone weights are numbers that you’ll memorize rather quickly (whether you intend to or not) if you use the LPP Rule, and it makes the bar math for any weight above these weights simpler, quicker, and harder to mess up.

We hope this helps you get stronger and live better!

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)

If you found this helpful, you’ll love our weekly email. It’s got useful videos, articles, and training tips just like the one in this article. Sign up below, and of course, if you don’t love it, you can unsubscribe at any time.

At Testify, we offer small group training, private coaching (in-person or remotely via Zoom), online coaching, and form checks. Would you like to get quality coaching from a Starting Strength Coach?

How to Warm-up for Lifting Weights: Stop Using Percentages!

/(A Blast from the Past article originally posted on 02/18/22)

For new lifters, figuring out what weights to select for your warm-up sets can be a bit mind-boggling, and for this reason, a percentage-based warm-up chart provides a handy approach. With that said, as you gain experience as a lifter, you’ll be better off if you eventually stop using this approach and instead make your own warm-up weight selections. In the long run, it’ll be faster and easier.

When structuring your warm-up sets, use the three principles below, and for more demonstrations, examples, and explanations, be sure to check out the included videos.

Warm-up sets should . . .

Principle 1: Prepare you for your work sets. Because of this, the weight for each set should gradually increase in roughly equal increments. The increases don’t need to be exactly the same each time - “roughly equal” is just fine - and if you have a bigger jump, it’s better to have it near the beginning of the warm-up than near the end.

Principle 2: Not exhaust you before you get to your work sets. Because of this, it’s wise to taper your warm-up reps, i.e., use fewer reps as the weight increases. At Testify, we usually recommend 2 sets of 5 reps with the empty barbell and then a 5-3-2-1 approach for the weighted sets (you’ll see this in the examples below). When starting out, you might not need this many warm-up sets.

Principle 3: Be convenient whenever possible and reasonable. Warm-ups don’t usually need to be all that precise, and the further you are from your work set, the less precision is required. For example, if your work weight is 245 lb and you’re deciding between 90 lb and 95 lb, go with 95 lb since it’s much simpler to load (one 25-lb plate per side compared to two 10-lb plates and a 2.5-lb plate per side). Additionally, there’s no need to use fractional plates in your warm-ups, and as you get stronger, you might not use 2.5 lb plates in your warm-ups either.

Below are a few good warm-up examples.

Example #1

Work weight: 105 lb

45 x 5 x 2

65 x 5 x 1

85 x 3 x 1

95 x 2 x 1

—————

105 x 5 x 3 (work sets)

Example #2

Work weight: 235 lb

45 x 5 x 2

95 x 5 x 1

135 x 3 x 1

185 x 2 x 1

215 x 1 x 1

—————

235 x 5 x 3 (work sets)

Example #3

Work weight: 385 lb

45 x 5 x 2

135 x 5 x 1

225 x 3 x 1

275 x 2 x 1

315 x 1 x 1

350 x 1 x 1 (needed another single)

—————

385 x 5 x 3 (work sets)

In the examples above, if the lifter is deadlifting, simply remove the empty bar sets (you’ll need bumper plates for any weights under 135 lb).

With practice, structuring your warm-ups becomes a very quick and easy process, and the longer you train, the more you’ll find that your first few warm-up sets don’t change very often from workout to workout, which makes things even easier.

We hope this helps you get stronger and live better!

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)

If you found this helpful, you’ll love our weekly email. It’s got useful videos, articles, and training tips just like the one in this article. Sign up below, and of course, if you don’t love it, you can unsubscribe at any time.

At Testify, we offer small group training, private coaching (in-person or remotely via Zoom), online coaching, and form checks. Would you like to get quality coaching from a Starting Strength Coach?

Why do I Keep FAILING?!

/Are you missing reps on your linear progression? Let’s address one potential problem, and it’s one that’s easy to fix.

Specifically, let’s talk about rest periods (i.e., how long you’re resting between sets). I know - not very exciting. However, rest periods are important because they can either support your training, or - if chosen poorly - they can derail your training.

When someone starts training with us here at Testify, we have a conversation on day one wherein we discuss rest periods, and during this conversation, we address two things:

1. Resting Between Warm-up Sets

The short version? You don’t need to do it. That’s right. Don’t rest between warm-up sets. The act of changing your weights will provide enough rest while you're warming up. These are warm-up weights and don’t require much of a break between sets. You are welcome to rest several minutes, but most people don’t have all day to train, and this is the place to save time in the workout.

One caveat - you’ll probably want to rest a few minutes after your last warm-up set, i.e., before your first work set, which brings us to . . .

2. Resting Between Work Sets

You definitely want to rest between work sets. When you’re getting started with the Starting Strength linear progression, somewhere between three and five minutes will probably suffice. Treat that range as a minimum.

Want to squat 225 lb like Sarah? be sure to rest long enough between your work sets.

Remember that the purpose of strength training is - not surprisingly - to get stronger. To get stronger, you need to do the prescribed training for the day - you need to lift what you said you were going to lift - and to lift that weight, you need to rest enough to complete all the reps of your work sets.

The Main Point

That last part is the main point - rest long enough to ensure that you complete the next set successfully. When you read “three to five minutes,” remind yourself that this is appropriate for when you’re starting out, and also remind yourself that this is a minimum. When things get heavier and more challenging, there will come a time when you need to rest longer - you’ll rest six minutes, seven minutes, etc.

Establish the Habit

One of the most enjoyable parts of lifting weights is . . . not lifting weights, so force yourself to get used to resting - even at the beginning of your strength training journey.

If it’s your second workout, take the three, four, or five minute break even if you know you could get back under the bar and complete the next set with a shorter rest break. Start establishing the habit of getting adequate rest right away in your training. If you tend to rush things, a timer can be a handy tool to ensure that you’re waiting long enough before starting your next set.

Practical Limitations

There are, of course, some practical limitations to how long you’ll actually rest, and you’ll notice that I’m not suggesting that you rest 15 minutes between sets. Even if a 10-15 minute rest period might be useful, it simply may not be practical in terms of your schedule for the day.

Wrapping Up

In general, though, rest long enough to ensure that you can complete the next set. Completing your work sets will allow you to get stronger, and in this way, you will still be making progress on your linear progression four months, five months, or even six months into it instead of missing reps in the first or second month.

It may help to remember that this isn’t conditioning; of course, there will still be a conditioning benefit, but that’s not why you’re strength training. You’re doing it to get stronger, so take the appropriate rest, and as always, we hope this helps you get stronger and live better.

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)