3 Pieces of Gym Gear That Separate Beginners from Serious Lifters

/If your gym bag only has shoes and earbuds, you’re probably just exercising. Exercise is certainly better than nothing - but if you actually train, then you show up with a few specific tools that quietly separate progress from plateaus.

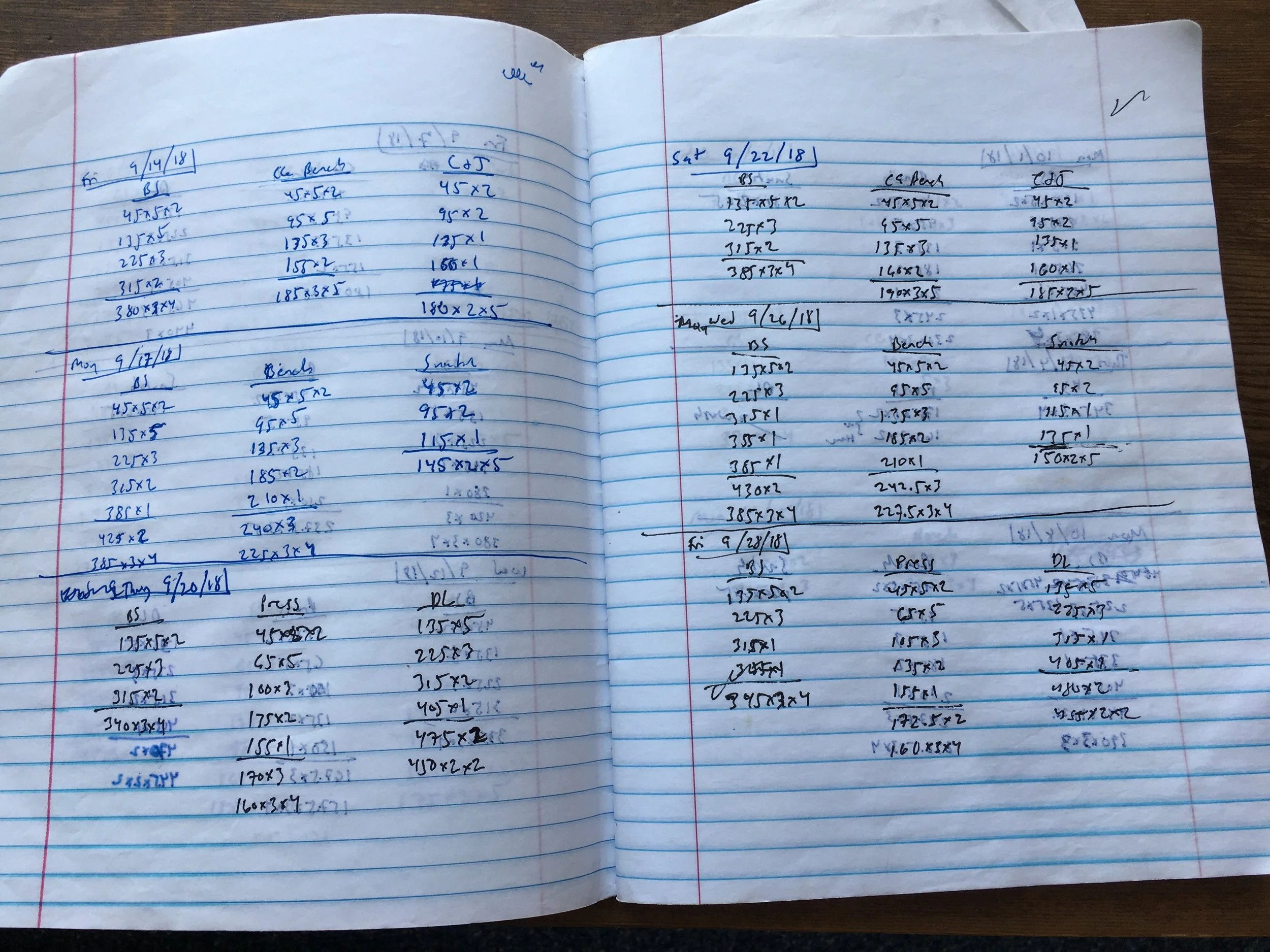

#1: Training Log

The training log separates training from exercise, and you are showing up to train.

Training means there’s a goal, which means there’s a plan - a program - designed to help you achieve that goal. That plan needs data, and your training log is that data. It’s the history of where you’ve been, and thus, it allows you to make decisions to help you move forward.

I recommend a paper notebook, but if you want to go the digital route, that will work, too. Record your warm-ups, record your work sets, record the cues you should be using, and before you walk out the door, record what you plan to do next time.

The training log is your most important piece of training equipment - more important than your shoes, belt, barbell, etc. All those items are replaceable, but your training log is specific to you, so be an intelligent lifter and start using a training log today.

#2: Chalk

Any decent, dedicated barbell gym should provide chalk for you, but most commercial gyms (i.e., globo-style gyms and chain-gyms) won’t. If your gym doesn’t provide it, there are two solutions - either buy your own chalk or find another gym.

Correctly chalked hands

Seriously, it’s that important. Sneak it in if you need to or use liquid chalk, but if you care about your training, this is nonnegotiable. You use chalk for the same reason climbers and gymnasts use it - friction. It absorbs the natural moisture and oils in your hands so that you have better - much better - grip on the bar.

#3: Fractional plates

Early in your training career - within the first month or two - you’ll need to start using fractional plates on your press, bench press, and possibly your olympic lifts. Females and older folks will find them useful for the squat and deadlift as well. Sadly, commercial gyms won’t have these, so at the very least, go out and get yourself a pair of 1.25 lb plates. Even better, purchase a full set of fractional plates, which includes a pair each of 0.25 lb, 0.5 lb, 0.75 lb, and 1 lb plates.

The ability to make a 2.5 lb jump (i.e, using a 1.25 lb plate on each side of the barbell) is hugely useful to making continued progress on a number of the lifts, and the ability to make even smaller jumps (e.g., a 1 lb jump using two 0.5 lb plates) is beneficial for many people as well.

If you take your training seriously, have these pieces of equipment when you train. Your results - and therefore your strength - will thank you.

As always, we hope this helps you get stronger and live better.

-Phil

PS: Whenever you want even more Testify in your life, here are some free resources:

Book a free intro and strategy session with us HERE.

Pick up a free copy of Testify’s Squat Guide: 12 Tips to Improve Your Squat Now HERE.

Get our free weekly email - containing useful videos, articles, and training tips - HERE.

Follow Testify on Instagram HERE.

Subscribe to Testify’s YouTube channel HERE.

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)