The Squat: Don't Be a Moron

/A lot of good advice in life can be summed up with the phrase, “Don’t be a moron,” and racking the squat is certainly no exception.

Listen, in the time it took you to squat your work set, the hooks (you know - the things the bar rests upon in the rack) didn’t go anywhere, so when you rack the bar, quit looking for them. Some lifters are either under the impression that their hooks have the ability to wander off while they squat, or they think they have incredibly cruel training partners who will steal their hooks while they squat.

You, however, are not one of these lifters. When finished with your set of squats, you just keep looking at your focal point (the same one you stared at while squatting) or you look straight ahead, and you then simply walk the barbell forward until it hits the uprights, whereupon you set it down - magically - on the hooks. You know that if you stay nice and tall as you walk back to the rack, hitting the uprights guarantees the bar will be over the hooks.

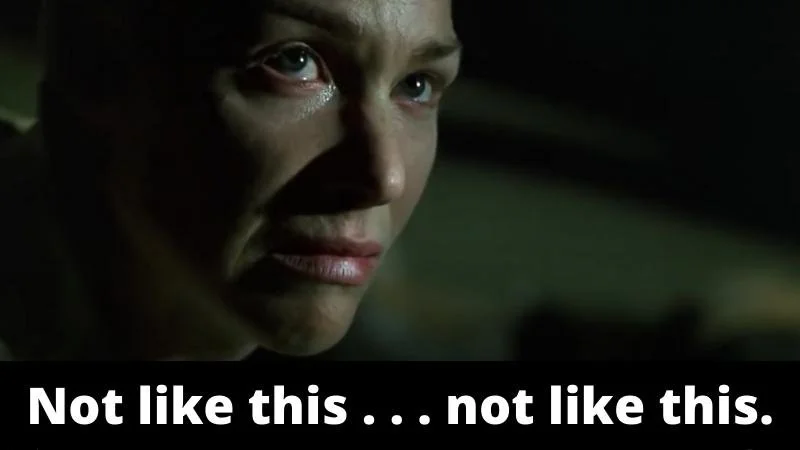

You also know that if you develop the silly-looking habit of craning your neck to look for the hooks, you’ll tend to walk the bar back to the rack in a rather cattywampus fashion, and one day, you’ll eventually miss one of the hooks (i.e., the one you’re not looking at). This makes for a wonderful YouTube video but a rather disastrous training experience. Fortunately, you don’t do this.

But . . . perhaps your friend does this. In this case, be sure to tell him, “Hey - don’t be a moron.”

As always, we hope this helps you get stronger and live better.

(Some links may be affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, Testify earns from qualifying purchases.)